We have one person with a mental-health problem. Helping her deal with that problem is the humane thing to do. What do you say we do that?

Many of us either have mental-health issues or know someone who does. It would probably be more accurate to say that most of us either have mental-health issues or know people who do. That’s how common psychological problems are.

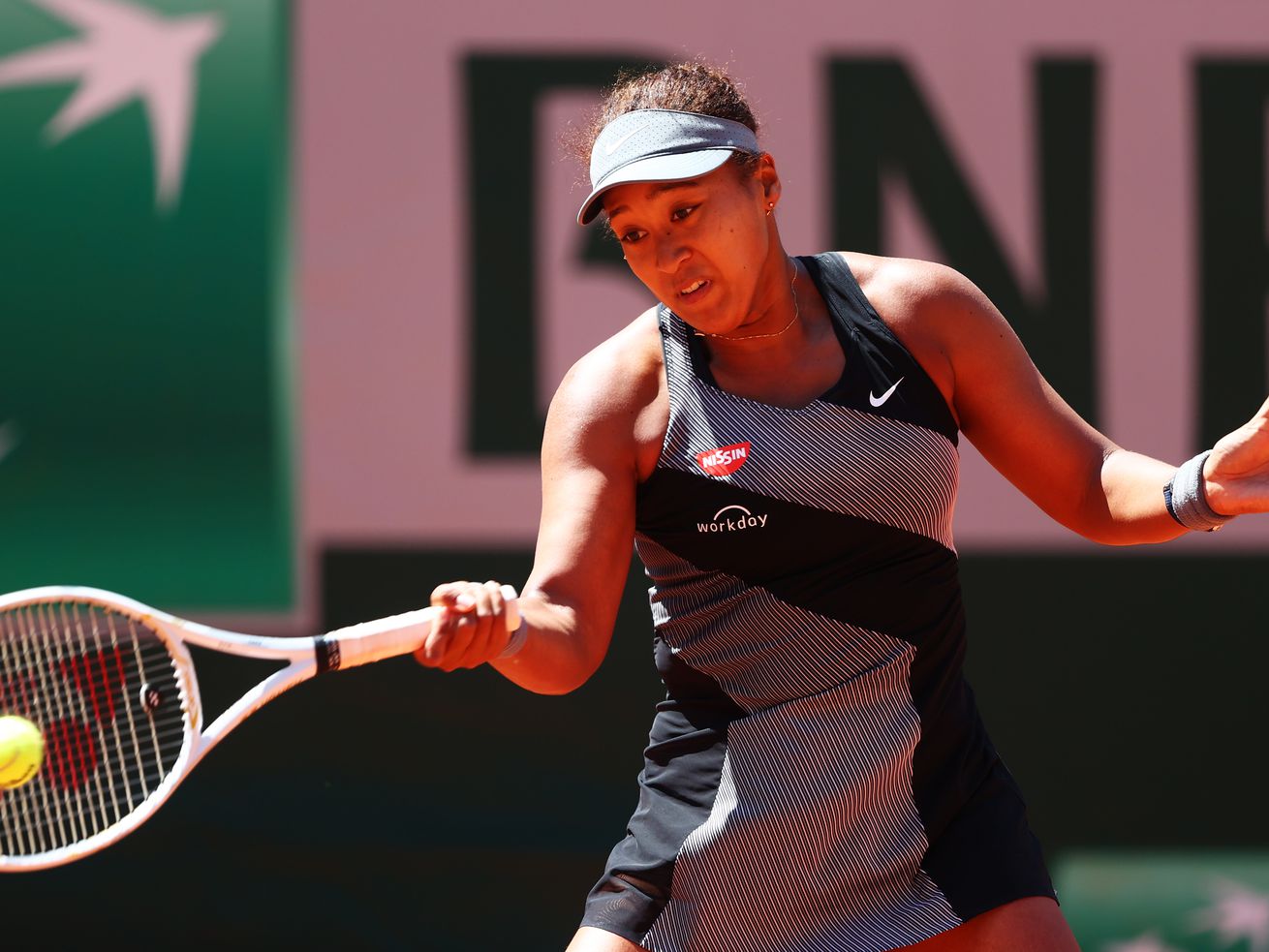

It’s why there has been such an outpouring of empathy for tennis star Naomi Osaka, who dropped out of the French Open because of anxiety and depression she says is caused, in part, by having to talk with the media. She refused to meet the press at Roland Garros, was fined by tournament officials and finally withdrew after they suggested she could be disqualified from the event.

We don’t like to see anyone suffering, but when the suffering is so public and when the sufferer is so well-known, it magnifies everything, including the reaction. We want to help Osaka. We want to protect her. We want to heal her.

This is where it gets complicated. Osaka initially cast the issue as something bigger than herself, saying it was cruel to subject players to intense questioning from media members after a match, especially a loss. Later, she brought the discussion to the place where it should have been in the first place, that press conferences are extremely difficult for her. It was too late. The media was painted as a collective ogre, and that was that.

The bigger question is not how to get rid of prying, indelicate reporters but how to deal with athletes who are battling something bigger and more powerful than any opponent they might face. Ninety-nine percent of the press conferences I’ve participated in have been docile affairs, with reporters going out of their way to be fair and professional. But to someone with problems such as Osaka’s, my “fair and professional’’ might be her “antagonistic and destructive.’’

Should we change everything for one player who says she’s paralyzed by anxiety before press conferences? Should she be exempt from the requirement most professional sports have that athletes must speak with reporters after games? Would not having to do so give her a competitive advantage over other players? Would it lead conniving performers to claim that they, too, have psychological problems that should excuse them from the stress of media questioning?

As I said, complicated.

Eliminating press conferences is not the answer. That would be the biggest knee-jerk reaction in the annals of jerking knees. Fans and media alike want answers after games. It’s not enough to watch an athletic event, say, “That was nice,’’ and go home. Given the opportunity, they’ll dissect a performance until it looks like shredded documents. Movie-goers have opinions after watching movies. Diners rate restaurants.

So this isn’t a media thing. It’s a people thing. It’s a human thing.

If reporters were taken out of the equation, we’d be left with the snake pit that is social media. If you think sportswriters are rude and ask inappropriate questions, I’d direct you to Twitter, where there are about 1 billion lowest common denominators. Escape from them is futile.

Here’s where I get to every time I think the Osaka situation through: compassion. We have one person with a problem. Helping her deal with that problem is the compassionate thing to do. What do you say we do that?

This is coming from someone who thinks dwindling access to athletes is one of sportswriting’s biggest issues. Over the past 30 years, pro teams have slashed our amount of time with athletes and cut the number of questions we can ask them. In the place of a fuller understanding of the people who play the games we watch are well-managed, extremely dull athletes.

But it wouldn’t kill us to give one tennis star a break. If we don’t, it might kill her.

Half of Michael Jordan’s mystique as a player was attributed to his indomitable will. He was born with a fire and a competitiveness his hagiographers say few humans possess. If that’s true, then it’s also true that some very talented athletes are born with the opposite mental makeup, with anxiety issues that seriously affect their performances. We wouldn’t think of penalizing someone like Jordan for being a domineering jerk on the floor, so why should we favor athletes who struggle psychologically?

Answer: Because none of us is better off with a fellow human being having a breakdown in full public view. Not us and certainly not the athlete.

If allowing Osaka to miss press conferences produces a wave of dishonest athletes opting out of those sessions, then officials can deal with it.

Until then, let’s be nice.