Imagine if I turned this article into a comic. (I’d do it, but I can draw about as well as I solve math equations.) In the first panel, you’d see Tim Samuelson and Chris Ware, who are actual, real-life people. Samuelson retired in January as Chicago’s first and only official cultural historian; Ware is a star in the world of cartooning, known for exacting, labyrinthine books whose aesthetic intricacy complements their profound insights on the human condition. Above their heads you’d see enormous speech bubbles, because I surmise two such knowledgeable people would have a lot to say. And they’d be talking about Gasoline Alley.

In the next panel, Samuelson and I are on the phone, and I’m asking him what was so innovative about that comic. “That was a pioneering comic strip that would tell an ongoing story,” he says of the Frank King–created work, syndicated out of the Tribune starting in 1918. “In fact, in that particular comic, the characters aged: There are characters that go from a baby and then you watch them grow up and go off to World War II.”

Moving back to that first panel, Ware and Samuelson’s conversation shifts to a plan they first discussed a few years ago to mount an exhibit on Gasoline Alley at the Chicago Cultural Center. New panel: Museum of Contemporary Art chief curator Michael Darling approaches Ware about doing a show on the history of Chicago comics. In Ware’s mind, a colorful sequence of Chicago comics unspools: Dick Tracy, Brenda Starr, Little Orphan Annie, the contributions of Black artists such as Jackie Ormes, Jay Jackson, and Leslie Rogers.

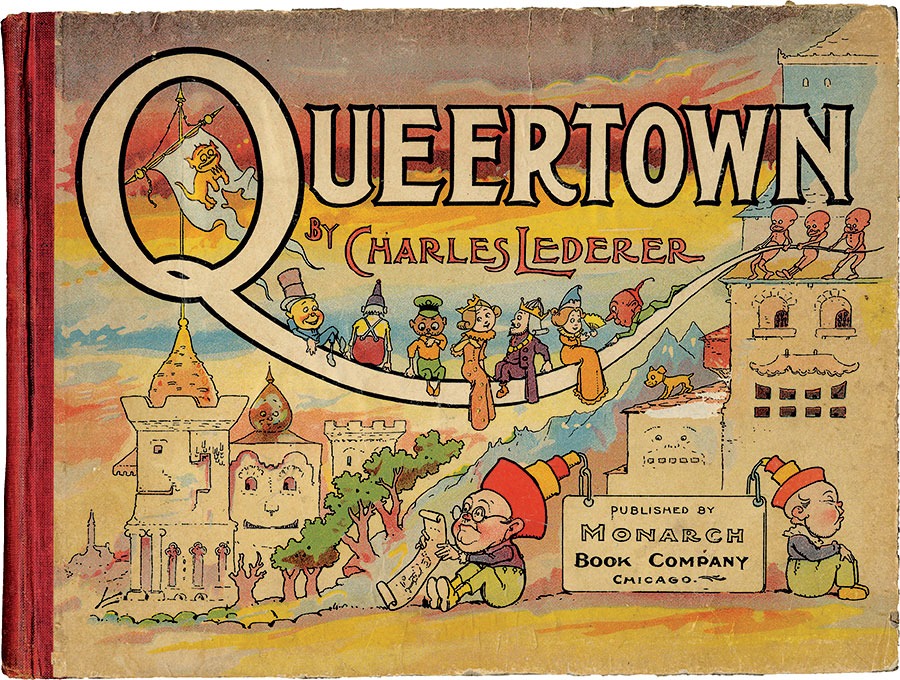

This all wound up resulting in two exhibitions, both running June 19 to October 3: Chicago: Where Comics Came to Life, 1880–1960 at the Cultural Center and Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now at the MCA.

Samuelson and Ware quickly realized that the entire history of comics in this city was too much to organize into one show, so they focused on the period covered by the Cultural Center exhibit. For its portion, the MCA brought on Brooklyn-based Dan Nadel, a renowned curator and author on cartooning. In the course of his research on Chicago’s Black cartoonists, he discovered far more material than he could include. As a result, he also compiled a collection of this underrecognized work: It’s Life As I See It: Black Cartoonists in Chicago, 1940–1980, which will be published June 1 by New York Review Comics. “It’s the first anthology of Black comic book artists anywhere,” Nadel says.

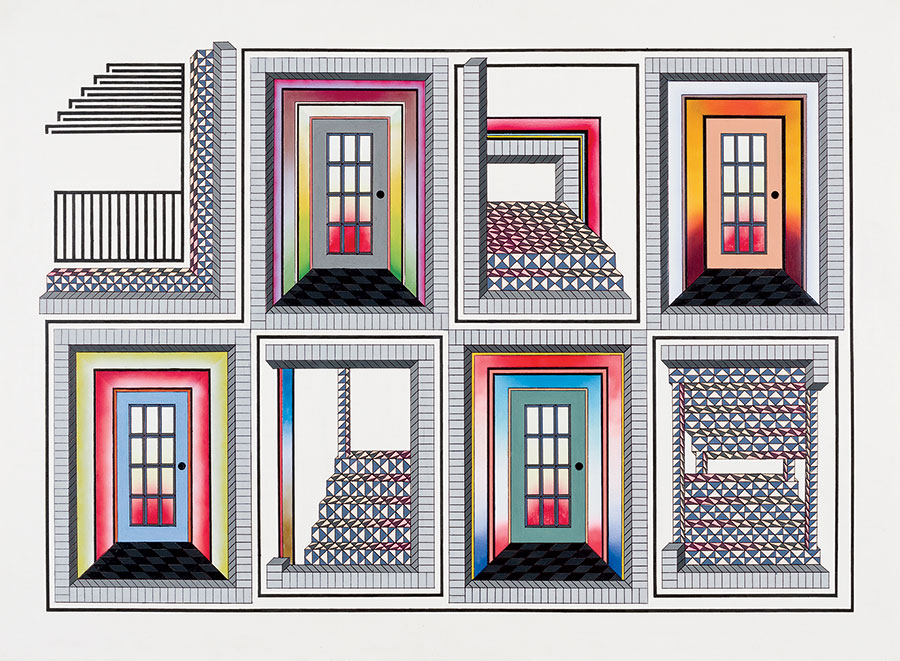

The exhibitions themselves will showcase exclusive and rare material. At the Cultural Center, you’ll be able to see copies of the first color strips in America, taken from Chicago’s Daily Inter Ocean in 1893, and the Tribune’s first color comics section. The MCA will display cartooning from such famous Chicagoans as Kerry James Marshall and Daniel Clowes and have rooms dedicated to single artists. That includes one for Ware, who is designing it himself using, he says, “essentially the same approach as I have for the Cultural Center.”

And what approach is that? “Lifting how one reads the standard two-dimensional rat maze of comics into three dimensions,” he says. “I have no idea if it works or if it’s completely insane.”